By Kenny Chumbley

He saw his story as a “modernized fairy tale,” but he put no fairies in it. He meant it to be without the “horrible, blood-curdling incidents” found in traditional fairy tales, but it has, possibly, the most blood-curdling incident in all of children’s fantasy literature. He was willing to leave morality lessons to educators, but every page teems with morality. Above all, he meant it to be a “wonder tale,” and in this he succeeded so well that no one disputes the right of L. Frank Baum to call his story The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

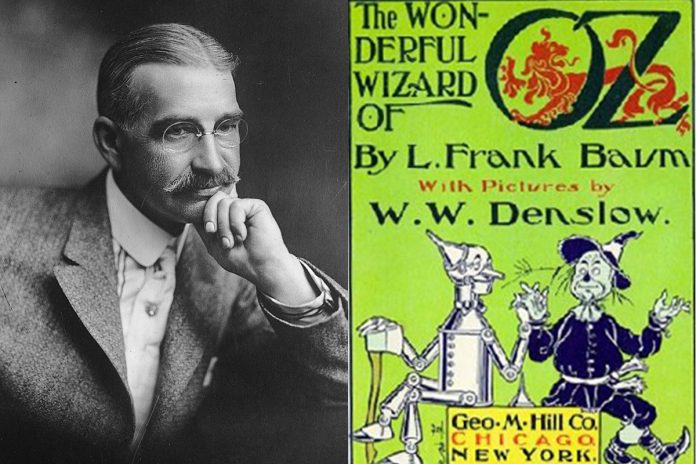

Baum had been a traveling salesman who spun stories for his children when he came home from work. When his mother-in-law suggested his stories would sell if he wrote them down, he did, and in 1899 submitted his manuscript to several publishers, all of whom rejected it. Finally, the George M. Hill Company offered to market the book if Baum and his illustrator, W. W. Denslow, put up the money for its publication. The book was titled The Emerald City, but because of a publishing trade superstition that a book with the name of a jewel in the title was bound to fail, Baum renamed it The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Ever since, it has been one of the brightest stars in the literary heavens.

The Wizard of Oz is a uniquely American fairy tale. Edward Wagenknecht, who wrote the first critical essay of the book in 1929, said it was “the first distinctive attempt to construct a fairyland out of American materials” (Utopia Americana, 17). Dorothy is from Kansas, the Wizard is from Omaha, and the Scarecrow is found in a cornfield (corn being a New World plant). Instead of goblins and fairies, there are Munchkins and Winkies, etc.

In the book, Oz isn’t “somewhere over the rainbow” but is in the middle of a great desert that none, attempting to cross, could survive. The many paradoxes in Baum’s story are readily seen in Dorothy’s companions. The Scarecrow wanted brains, but whenever a problem arose, he solved it. The Tin Woodsman wanted a heart, but when he accidentally stepped on a beetle, he wept till his jaws rusted shut. The Cowardly Lion wanted courage, but he was ever the valiant protector of the group. What these heroes had in abundance was humility—the starting point for all virtue—only, they were too humble to know it.

One day as Baum was telling his tale, a neighbor girl, Tweety Robbins, asked where the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman lived? Looking around the room, Baum spied a two-drawer filing case in the corner. On the top drawer were the letters A-N; on the bottom, the letters O-Z, and thus was born the name of the land we’ve all visited in our imagination.

Baum said his stories were for everyone whose heart was young. If you’ve grown up with The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and still love it, what a wonderful thing that says about your heart.

About the author:

Kenny Chumbley, a native of the Illinois prairie, is a minister, author, and publisher. He has authored one children’s story (Ol’ Pigtoes) and two fairy tales (The Green Children, the Literary Classics 2017 Enchanted Page Award recipient for best children’s storybook, and The Goblins Who Stole a Gravedigger, an adaptation of Charles Dickens’ first Christmas ghost story). He has also written and produced two musical plays based on his two fairy tales.