By Kenny Chumbley

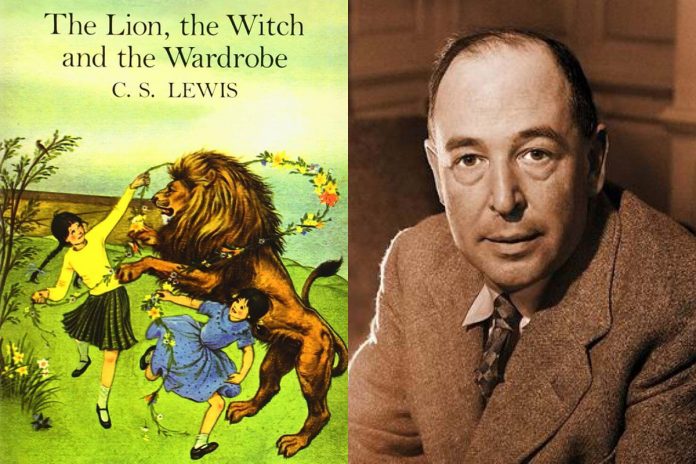

It is often the case that children are introduced to the genius of C. S. Lewis through his fantasy series, The Chronicles of Narnia. But, surprisingly, this series, beloved by millions, nearly never happened due to the criticism of Lewis’s close friend and colleague, J. R. R. Tolkien.

According to his biographer, George Sayer, Lewis first thought of writing a children’s story in September 1939, but it would be nearly ten years before The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe was published. The idea for the book came from the interest a child, who was staying at Lewis’s home near Oxford (the Kilns) during the Blitz, showed in an old wardrobe. When the child asked if she could go inside and see if anything was behind it, Lewis’s imagination was triggered. “All my seven Narnia books . . . began with seeing pictures in my head. At first they were not a story, just pictures. The Lion all began with a picture of a Faun carrying an umbrella and parcels in a snowy wood. . . . Then one day . . . I said to myself: ‘Let’s try to make a story about it.’”(1) And he did.

But he was in for a shock when he read the manuscript to Tolkien, who reacted with “a snort of contempt.”(2) The author of The Hobbit thought Lewis’s “book was almost worthless . . . a jumble of unrelated mythologies [with] quite distinct mythological or imaginative origins.” Tolkien thought it a terrible mistake to put disparate mythologies into a single story, and he never changed his view.(3) That their friendship continued unabated is testimony to Lewis’s belief that since friendship, though angelic, is not a mutual admiration society, it “needs to be triply protected by humility if [a man] is to eat the bread of angels without risk.”(4)

Unlike Tolkien, Lewis didn’t hesitate to infuse his stories with moral values, and for this he was widely criticized. An example involves Eustace Scrubb, introduced in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. When the ship, the Dawn Treader, lands on an unexplored island, Eustace, a selfish, whinny brat, goes exploring and stumbles upon a dragon’s lair that contains a dragon’s treasure. As he falls asleep, greedy thoughts fill his head. When he awakens, to his horror, he discovers he has taken on the form of a dragon. “Sleeping . . . with greedy, dragonish thoughts in his heart, he had become a dragon himself.” Your heart will always be where your treasure is, said a Galilean carpenter. And what you are in your heart is what you are.

Lewis filled Narnia with theological depth and mythical quality. He didn’t deliberately set out to promote Christian belief in the guise of fantasy; in writing as he did, he was just being true to himself.

So let the critics carp; millions upon millions of admirers cannot all be wrong.Nothing can change the fact that Lewis’s Narnia books, along with Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, represent the most remarkable phenomena ever seen in the long history of fantasy literature.

Footnotes:

[1] Lewis CS. “It All Began with a Picture,” Of Other Worlds (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: New York, 1966), 42

[2] Carpenter H. J. R. R. Tolkien (Houghton Mifflin: Boston, 1977), 204

[3] Sayer G. Jack, C. S. Lewis and His Times (Harper & Row: San Francisco, 1988), 189

[4] Lewis CS. The Four Loves (Mariner Books: Boston, 1960), 87

About the author:

Kenny Chumbley, a native of the Illinois prairie, is a minister, author, and publisher. He has authored one children’s story (Ol’ Pigtoes) and two fairy tales (The Green Children, the Literary Classics 2017 Enchanted Page Award recipient for best children’s storybook, and The Goblins Who Stole a Gravedigger, an adaptation of Charles Dickens’ first Christmas ghost story). He has also written and produced two musical plays based on his two fairy tales.