Book Review by Rafael Peñas Cruz

I got to know Debasish Lahiri’s work in my capacity as translator and publisher with Goat Star Books, a London-based publishing project specialised in poetry translations to and from English. My then recent publication of a bilingual English-Spanish collection of poems by Punjabi poet Danial Andrew Danish attracted his attention through common friends in social networks and, as a result, we developed a friendship leading to him sending me two of his published books: Tether that Light and Poppies in the post.

As with the work of Danial Danish, I was struck by the great quality of Debasish Lahiri’s poetry, and his confident use of English as a vehicle of expression despite not being his mother tongue. I found very interesting this “appropriation” of English by writers who, like me, a Spaniard born and bred, decide to use a different language from their own as a means of expression by choice and not necessity. There is a certain freedom in that choice, a liberation from the tyranny of tradition, allowing you to innovate, to be more yourself, paradoxically as it may seem. As a publisher of poetry in translation with a vocation to be a bridge between cultures, I felt that this aspect of their poetry was strongly related to the Goat Star Books project.

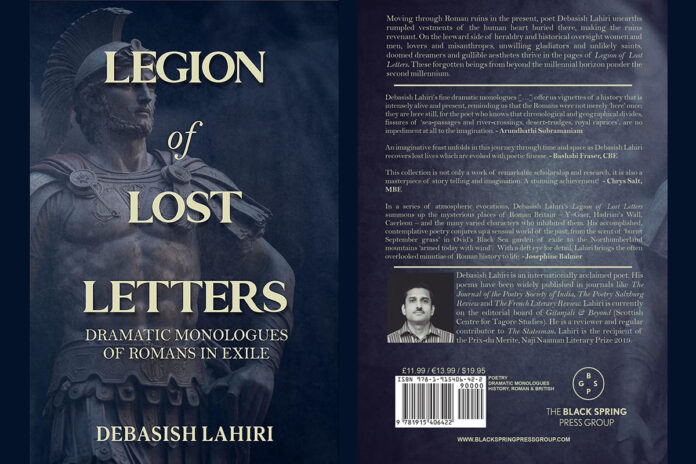

Debasish’s latest book, “Legion of Lost Letters”, seemed to go deeper down that interesting road. It was a reimagining of what Roman soldiers and ancillary staff posted in Hadrian Wall would write home. This was postcolonial, but not as we have known it till now, since Edward Said´s seminal work “Orientalism” of 1978, which opened up a reassessment of how Western culture had used art and literature to underpin and justify the imperial projects of the different European powers.

Now it was the other way round. Here was a son of the Empire recreating what it would be like for those colonial powers to have been themselves colonised in previous times. An inverted cultural appropriation if you like. But shouldn’t culture circulate? I believe it must, so I found Debasish’s proposal very innovative and groundbreaking.

I took Legion of lost Letters as reading companion to a trip to Japan, mostly exploring the northerly island of Hokkaido. Despite globalisation and the greater uniformity that it has brought, Hokkaido was still as distant from me as Britain would have been for the Roman soldiers posted there in the first three hundred years of our Christian Era, who are the subject matter of this beautifully evocative collection of poems by Debasish Lahiri.

Apart from the opening one, which gives voice to Ovid at his exile in Tomis, each of the twelve poems included is a letter written home by one of those Romans. They are soldiers, artists and chancers, women of marriageable age, slaves, a whole panoply of characters living far from the comforts of the so-called civilised world. They are all masterfully conjured by the poet´s voice.

The whole world of that frontier land is brought alive in all its liveliness and complexity: the interaction between the barbarian Celts and the invaders, the politics of the Empire as well as the personal conditions of each character. Everything is presented with expert brushstrokes, even the interaction between past and future in some case, as in a Mrs Williams of Usk, shopping in a timeless high street.

What comes across is Debasish’s knowledge and familiarity with his subject matter. His letter-poems are full of references that show great erudition and serious and sympathetic research. But what impresses me most is the imaginative power of the poet to put himself in the minds of those people, respecting their individuality and the context in which they lived, while bringing them in line with our present time. We identify and recognise them, their motifs, their feelings, their hopes and disappointments are the same as ours. They relate to their new land and to those they find there as we would if we found ourselves in their position.

The fact that Debasish is from Kolkata adds an extra layer of meaning, for this is a book written in English by a man from a country, India, which would later be colonised by those British tribes that had been previously colonised in their turn by the Romans two thousand years earlier. The point that the book makes is thus a poignant one, and one that the modern orthodoxy of postcolonial studies often refuses to accept: the idea that we are all colonisers and colonised in some way or other, that we are all the product of a cross-pollination of civilisations, of encounters and conquests, often violent, always complex, ever fascinating.

So, as expected, it proved to be the perfect companion read for my expedition into the far north of Japan. By the Sea of Okhotsk, the indigenous Ainu people had lived peacefully until brutally colonised and acculturated by the Japanese in a similar way as Britain was by the Roman legions of Caesar Augustus. In the Ainu I recognised the Celts, and in the dispute between Russian and Japan for the Kuril and the Northern Isles, I saw the scrambling for power and territory that is behind the expansion of all empires, whether Roman, British or Moghul. The history book on the shelf, to quote Abba quoting Hegel, is endlessly repeating itself, and “Legion of Lost Letters” has a deep message to tell.

I find Legion of Lost Letters an important book. I am grateful to Debasish Lahiri for writing these poems, which open new panoramas in the landscape of the postcolonial literature, adding a much needed, more nuanced approach to a discipline or genre that is in danger of becoming clichéd.

(Legion of Lost Letters – Dramatic Monologues of Romans in Exile– Published by The Black Spring Press Group, UK)

About the Author

About the Reviewer

Rafael Peñas Cruz is a writer, translator and retired lecturer of Hispanic Culture and Society. He has a degree in English philology from the University of Barcelona and a master’s degree in Hispanic studies from Birkbeck College, University of London, the city where he has lived since 1992. In 2004 he published his first novel in Spanish, Las dimensiones del teatro, and in 2009 his second novel, Charlie, also in Spanish won the 5th edition of the Terenci Moix Prize for gay literature. His website https://quincejellytin.com/ is a project that combines photographs and text to give narrative form to people’s experiences, creating an archive of human experiences. This project was the basis from which he started the BTV program Al cel obert, on local television in Barcelona. In 2020, he and Catalan artist Mayca Martínez Victoria published “Una imagen y mil palabras,” a book that explores the relationship between art and life, between words and paintings, and between literature and reality. In 2020 he set Goat Star Books, an independent publishing project specialising in poetry translations as a bridge between people and cultures.