By Asya Pekurovskaya

*

Quest for Glory and Quest for Word: Case of Bro and Case of Bo is a 156,000-word mixed genre manuscript that weaves together autobiography, essay, and literary criticism to explore the lives and legacies of two Russian poets, Joseph Brodsky and Dmitry Bobyshev, who were part of Anna Akhmatova’s inner circle during her final years (1889–1966).

Quest for Glory and Quest for Word delves into the intricate dynamics between Joseph Brodsky and Dmitry Bobyshev, irreconcilable rivals following Akhmatova’s death. Brodsky’s meteoric rise to fame culminated in his emigration to America in 1972 and a Nobel Prize in 1987, though his journey was marred by personal and professional struggles. Conversely, Bobyshev remained in the shadows for much of his life, only to be later recognized for his enduring literary brilliance, praised by critics as “belonging to the masterpieces of world literature.”

Below is a chapter extract from the book.

*

Chapter 22. “The Beasts of Saint Anthony”

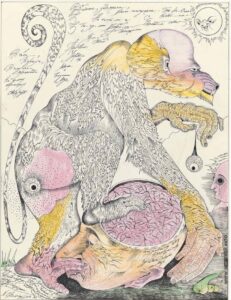

My title echoes the moniker given by Bo to his elegantly published book of poems, illustrated by Mikhail Shemyakin. However, the introduction (Lure of Creativity) immediately guides the reader towards temptation. But what kind of temptation? And what might have sparked it?

Before the visual encounter with Shemyakin, there was a virtual onnection. In the foyer of the conservatory, where Shostakovich’s concert took place, an exhibition of the “already scandalous” Shemyakin was displayed. “On the walls hung meat carcasses, brazenly spreading their ribs, painted in rough strokes in the manner of Chaim Soutine. They merely hinted at the future contour, which, however, was already evident in his book illustrations. It was towards these showcases that I was drawn” [Bobyshev, 2008, pp. 184-185].

The artist who was destined to reshape our concept of reality, submitting it to his wild imagination, had already found a permanent place in Bo’s fantasies. Shemyakin’s creatures were longed to be captured on paper, while the communal apartment in Leningrad, the digs of residents who yet hadn’t considered emigrating from, now appeared to the poet as a temple inhabited by muses. And here it is, its vision:

“In the middle of the room stands an open grand piano. Nearby is a Gothic chair with a straight, high back, to which a sheet of music is pinned: “Bach’s Chorale. Eighteenth-century notation,” reads Bo. “The original.” A bit further away hangs a lamb carcass, hooked and spread. Its sides are weathered, with tufts of fat in the abdomen turning yellow. In front of the carcass stands an easel with a stretcher and lumpy layers of paint applied over the underpainting. On the walls—paintings, etchings, still life drawings, and nudes, along with photographs of the master in whimsical poses—are surrounded by antique or theatrical props: a pipe, a cleaver, a tricorn hat, oddities, and trinkets” (Bobyshev, 2008, p. 185).

The years fly by. Mikhail Shemyakin is no longer the “scandalous” stranger to the world of art but has become, as is customary in our country, a universally recognized master. Bo has also progressed, having impressed connoisseurs with his “keen ear,” as Mandelstam might say, blending brush with pen. The air is ripe with the impending meeting of two titans. After all, Shemyakin has taken on the task of illustrating Bo’s poems, leaving the selection of texts to the author.

“I accept the offer with gratitude. But I also feel an obligation! The poems that have already been published are, it seems to me, not suitable for a joint project. I undertake to compose a completely new text, especially and only for you. Will you agree to wait for about six months, well, maybe a little longer? We sealed his consent with a handshake.Well, it was already a purely American ‘challenge’: what plot could encapsulate the dark, vibrant personality of the artist, his environment, and his works? As the verbal magician Mikhail Kuzmin once asked:

Where can I find the words to describe the stroll,

Chablis on ice, a toasted roll?

“Here, instead of a simple roll—mummies, scars, noses. Yet, alongside these—European style and elegance!” And in the content, in the plots—mysticism, a compelling yet repelling mystery… And the first word that comes to mind—temptation. Temptation—of whom?—of Saint Anthony, of course, and, of course, primarily of Bosch’s Saint Anthony… Temptation—by what?—not merely by erotic enticements (though those too), but by fear, by the heat of massive flesh and, conversely, its vanishing illusoriness, by the madness of absurdity, and equally by logical reasoning, by surrealism, by the horror of the dark well within oneself—all that distracts the saint from his spiritual asceticism.

The second word came to mind—bestiary, a gallery of fantastic beasts, semi-mythical monsters that seized not only the mind of the Nile ascetic but also the minds of his contemporaries. What if I were to combine both medieval legends into one? That would be the text Shemyakin could not resist, that would be him! But where to find all these delightful legends, of which I have only fragmented, albeit vivid, knowledge? Of course, in our famed library, which I sometimes criticize… Up the polished gray-marble steps, past the four panels with allegorical maidens, the maps of the Americas, the starry sky, and the Arctic, past the changing sheets of the Audubon (Ornithological) Society—what bird is on display today?—and into the Slavic department of the library… That’s where I finally appreciated what Ralph Fisher had accomplished!” [Bobyshev, Ibid, p. 185].

Next comes a brief conversation with the understanding bibliographer, Helen Sullivan, which ends in success: “We have just received the album ‘Medieval Bestiary,’ and it’s currently being processed. It’s a beautiful edition with color reproductions. The original manuscript is in the Public Library in Leningrad. If you need it for your work, I’ll pause the processing. Keep it as long as you need.

She went to get the book <…> and I soared away like a steppe red-tailed hawk (Buteo harlani) from the Audubon album, clutching the precious prize in my talons” (Bobyshev, 2008, 185).

As I leaf through the brilliantly completed work, I begin to sketch a tentative plan of action. The first step is the library in Freiburg, not particularly renowned but nonetheless curated in the taste of Martin Heidegger himself. But did Heidegger’s interests extend to bestiaries? Here’s the answer. I pull a hefty volume of the Book of Beasts off the shelf. “What is a bestiary?” What do I need to know about bestiaries? “It is a collection of quotations from classical authors, such as Pliny the Elder.” I flip further. “The text is purely didactic, with each chapter concluding with a moral, and the audience is monastic” (Book of Beasts, 2020, p. 67). However… By the mid-13th century, the didactic tone begins to fade. An example is found in the story “The Cat and the Hawk.” The artist, the commentator writes, “does not moralize but disorients: he intersects the familiar with the strange. The dark blue background, studded with moons and stars, suggests a nocturnal scene, but the numerous moons are not naturalistic” (Book of Beasts, 2020, pp. 79–81).

And so I think. The rebuff of the didactic tone could not provoke a break with tradition. Rather, it left tradition in the background of history, giving authors an everlasting choice, which Bo voices: “But this isn’t a commission, it’s merely a collaboration. Yet it must be first-rate and stylish, nothing less than what Shemyakin does. Why not draw a drop of the fermenting brew from which the artist himself draws? That’s an idea… And an opaque ‘murkiness’ was sown in the prayerful consciousness of the holy ascetic—a tiny bit, just a speck of dirt, without which, it turns out, there is neither creativity nor life itself… And so it began!” The album from the Public Library turned out to be an invaluable aid—a veritable treasure trove of inspiration. To the beasts, even those existing in nature, not just mythological ones, were attributed such vivid fabrications that they no longer represented absurdity or ignorance but pure artistry… Surrealism!”

Vivid fables… a temptation to creativity… What are these if not symbols with lost links of meaning: illogical and convincing, like witchcraft and miracle. This is called poetry. The beast irresistibly attracts its victim… with the aroma of its breath! Let’s take, for example, a panther.

Bo’s enchantment began with the “Panther.” Of course, the “panther” was not meant as a biological species but rather a genus of beasts: perhaps Panthera leo (lions), or Panthera tigris (tigers), but more likely Panthera pardus (leopards). And the enchantment, as stated, began with fabrications “convincing through their illogicality.” However, illogicality can only persuade when juxtaposed with logic. “No matter the order of the creatures, the lion is always first, as in the beginning of the text, it is designated as the King of Beasts” (Book of Beasts, 2020, p. 7).

Beyond the bestiaries, the panther-lion might be denied primacy, but never its sorcery. For instance, when Menelaus tried to free Odysseus, held captive by the sea god Proteus, “the old man did not forget his sorcery: suddenly he turned into a fierce lion with a huge mane” (Lauenstein, 1996, p. 300). In bestiaries, however, the panther-father’s sorcery, who “breathes life into his offspring by breathing into its face,” is tied to the legend that lion cubs are born dead and are revived within three days by their parents, who lick them and breathe on them (Book of Beasts, 2020, p. 90).

How does Bo respond to this legend?

The revival of the cub is linked to a return to its conception, that is, to a ceremonial act—a coitus. Accordingly, the lion lineage is represented not by the father lion, but by the lioness, who is destined to expel the stillborn cub from herself. In this moment, unaware of what is to come, she exudes monarchical majesty—a queen, radiant with gold and her spotted skin, which absorbs both the moon

and the sun. Right now, she is a deadly beast, and the sign of her lethal ferocity is the triple row of teeth on both jaws:

“What delicacy and what a vigor!

Her vulva curls, especially emitting early rigors…

And sweating not of virgin loving pearls,

but of the history of love of former lovers.

She is- a captive, but besides

and more, she is a mistress:

The queen in gold, all nude, on every side,

with spots of creeping moons and suns, reposing,

among the scents, in provocative poses.

with her inhale that roams and prods the tropical expanses,

attracting hearts, as living meals

For lucky ones – the dying bill.

Such are the tigress’s dances.”

The stillborn cub, carried in her ‘blessed womb,’ mirrors the history of the mother’s own birth.

“Bo’s chosen title for his bestiary references the temptations of a Christian hermit, a theme that fascinated the originator of the ‘evocative method” (by L.V. Pumpyansky), whose experience Bo seems to have absorbed. This experience could be put to good use, considering our interest in the symbiosis of artist and poet, perhaps even in ekphrasis. So, long before Bo, medieval bestiaries had captivated Gustave Flaubert (1821–1880), the author of the drama The Temptation of Saint Anthony. There is evidence that “the image of the Christian hermit accompanied the writer for nearly thirty years. Flaubert completed the first version of the drama in 1849, before his journey to the East and the creation of the novel Madame Bovary. This version was tied to an important decision—to become a writer. The second version emerged in 1856, preceding Salammbô. The third version coincided with the work on Bouvard and Pécuchet. This novel remained unfinished, while the drama on Saint Anthony, published in 1874, became the writer’s last major work” [Modina, https://doi.org/10.4000/flaubert.622].

The inspiration for the drama was a painting by a Flemish artist. “In Genoa, in the Palazzo Balbi, Flaubert first saw Bruegel the Younger’s The Temptation of Saint Anthony [1550–1575], which inspired him to conceive the drama of the same name. Upon visiting the Milanese Ambrosiana Library, he was already enthusiastically perceiving other works by the artist, whom he called ‘my Bruegel.’ The drama about Saint Anthony would become the writer’s lifelong work” (Flaubert, 1995, p. 8).

Following in the footsteps of the biblical Adam, Flaubert gives the beasts mythic names. In particular, in his drama, which remains “the least studied, the least read, and the most mysterious of all his works” (Bruneau, 1990), а colossal red lion, with a grotesque human face and three rows of razor-sharp teeth, is named the ‘manticore. This is how the lion introduces itself in the author’s imagination: “The gleaming crimson of my skin merges with the brilliance of the vast sands. I exhale the terror of the deserts through my nostrils. I vomit plague. I devour armies when they venture into the wilderness. My claws are curved like augers, my teeth are serrated like a saw, and my coiled tail bristles with darts, which I hurl left, right, forward, backward. Here! here!” The manticore hurls needles from its tail, which scatter like arrows in all directions. Drops of blood fall like rain, snapping against the leaves” (Flaubert, 1999, p. 195).

As if the monstrous manticore weren’t terrifying enough, Flaubert introduces another nightmarish element: “We leap from branch to branch to suck eggs, and pluck chicks; then we wear their nests on our heads like caps. We try to tear udders from cows and scratch out the eyes of lynxes; we defecate from the tops of trees and are unashamed to display our disgrace in broad daylight. Tearing flowers, trampling fruits, muddying springs, raping women, we rule over all—through the power of our muscles and the fury of our hearts” (Flaubert, 1999, p. 194).

To the trials of horror, Flaubert adds the trials of gourmet delicacies. “On the tablecloth, rippling like a sphinx’s bands,” lay an array of temptations “huge chunks of bloody meat, large fish, birds still in their feathers.” Then, amidst this feast, Anthony’s eyes fell upon the boar, steaming and monstrous, filling him with forbidden pleasure: “quadrupeds in skins, fruits almost the color of human flesh, and pieces of white ice and vessels of purple crystal sparkle with lights. Anthony notices a boar at the center of the table, steaming from every pore, with its legs tucked in and its eyes half-closed, and the thought that he could eat this monstrous animal gives him immense pleasure. Then there are dishes he has never seen before: black stuffing, golden jelly, stew where mushrooms float like water lilies (nénufars) on ponds, whipped cream as light as clouds” (Flaubert, 1999, p. 41).

But Bo, having barely left the library with the volume of medieval Bestiaries, dealt with his “precious prize” in a manner reminiscent of Flaubert: “I deliberately welcomed this touch of madness into my mind, viewing it as a crucial, though unstable, support for artistic skill—much like a tightrope is for an acrobat. “And the result? My inner juggler, unsteadily balancing on this tightrope of madness, conjured a series of bizarre images: fish, insects, exotic birds, and truly bizarre hybrids, born of the pastoral imagination of ancient Greeks. Not bad, even quite ‘appetizing,’ was the description of the consumption—using bamboo chopsticks—of the brain of a living monkey, delicately seasoned with soy sauce, and enhancing the eerie delight of the grotesque feast!” (Bobysh, 2008). And the result? My inner juggler, unsteadily balancing on this tightrope of madness, conjured a series of…

Flaubert’s mythical monkey, called Cynocephalus[1] (Bruneau, 1990) is resurrected in the first four quatrains of Bo’s poem “The Monkey”.

“An arm–legged, a batt–faced,

A cackling hoot with a tail,

With flabby boobs – What a showcase

And a perfect fit for a tale?

To boot, he is pleased and proud

Of his ear–like gluttonous snout

That’s gulping down the flies,

Scratching his itching thighs,

A snap of an old bag unclad.

Suddenly, from the front–hinder

Where About bananas linger

Monkey’s eyes, as a crazy spieler

Stare at you like tactor or feeler.

Shall you get shaken or snigger?

Will he munch on your nose, then spit it out?

Scoop off your eye, then suck and blot?

There is, of course, a curative clout

For a jumping beast – a hunter’s shot”.

Bo does not succumb to Flaubert’s ambitions nor does he experience the horrors of Saint Anthony. Instead, he introduces the theme of punishment for those who consume monkey brains. Some claim that monkey brains are sometimes eaten raw, immediately after or even before the monkey is killed. The monkey is drugged. It is placed under a table with a hole in the center. Diners see only the top of its head. The skull is sliced open, revealing the raw, quivering brains of the still-breathing monkey. This dish is reportedly considered one of the most expensive in Asian restaurants and is supposedly served mostly illegally. However, the British newspaper The Guardian reports: “The consumption of cooked brains from dead monkeys is possible, though highly unlikely, whereas the eating of brains from live monkeys is an artifice.”

But even into this artifice, Bo breathes new life, shifting the trial by gourmet delicacies from the category of Saint Anthony’s torments to that of the pleasures experienced by those who feast on monkey brains:

And a guillotine… In its ensuing slot

The injured neck is tightly caught.

The skull grimaces to its full content,

The body – under – doesn’t pretend.

But the eyes are vigilant. They attend…

His vault is cut and open aloof.

The crown’s removed from its helpless roof.

And the brain. Its gaze. But still the brain

As galaxies burn with its boundless pain.

A pinch of salt… Spices to ration,

Like rice vinegar. And, gentlemen,

Delight your palate with acceleration

With soya sauce as an extra pigment.

And with a chopstick select a gyros,

Not a worm. Worm’s zigzagging. Ouch!

But a treat that delights your paunch

And your guts to rumble like an in–tune guiro.”

“The trials of gourmet delicacies” in Bo’s work are intertwined with the metaphysical theme of the “sense of vastness of the world,” which inspired Pasternak to write the poem I Long to Go Home to Vastness (1931). While Pasternak viewed vastness as a reflection of his inner conflicts, Bo interprets it through the lens of existential temptation, experiencing it through Flaubert’s matrix of Saint Anthony’s temptations. This idea is echoed in Gennady Katsov’s extensive commentary on Bo’s collection The Sense of Vastness. Katsov traces the long journey of the lexeme “skull” from Shakespeare’s drama to Salvador Dali’s composition, immortalized in one of the seven photographs by Philippe Halsman (1951). Let’s listen to Katsov’s reflection:

“It [this composition – A.P.] was left to eternity in the form of a photograph: seven nude, supple female bodies intertwined so that the spaces between them eerily outline the hollow cavities of a skull, and the overall contour—this is the artifact of the skull itself. Besides the clear erotic component, there is a trace of the idea from several Buddhist sects that use human skulls as amulets <…>. When reading Bobyshev’s texts, one gets the impression that the image of the hollow skull is also necessary for the author as a counterbalance to his richly baroque lines, often excessive in their vitality, the energetic vividness of his poetic code, and the lifeblood flowing with the juice of love. It’s as though one side of the scale holds triumphant Thanatos, as it should, while on the other—boiling with passions, inflamed Eros” (Katsov, 2017).

Before returning to Salvador Dali’s composition in Philippe Halsman’s photographs in my commentary on the poem The Elephant, I would like to offer an illustration to Katsov’s thesis on vitality as Bro’s poetic code:

“but a propos de wines:

Chablis collects all silver, while gold is snatched by Rhine:

In California abundant is the vines,

That crawls into the verse like its majestic pines.

Shrimps’ tender cartilage, their perfect match

To revel in, or fatty oysters splashed with lemon sap;

Then trout with pine nuts, its fiery crunch

above the delicate pink kernel – perfect snap!

There palm hearts being lanced and mingled

Asparagus with Shakespeare, and bean sprouts as Proust;

and Joyce’s artichoke: its petals stocked with needles

Or soaked in marinade – all win in joust.”

D. Bo. “Feeling of Еnormity.” // Urban Life.

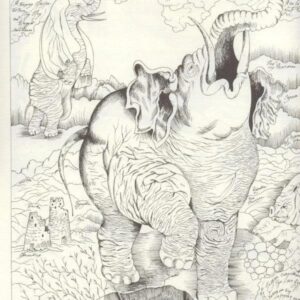

About the “Elephant” there exists the following description:

In the Book of Beasts, the elephant is described as follows:

“There is an animal called the elephant, which has no desire for coitus. The Greeks believe that the elephant is so named because of its enormous body, as it resembles a mountain, for in Greek, a mountain is called elephios. No animal appears larger. Indeed, the Persians and Indians place wooden towers on them and fight with spears, as if from a wall. <…> Moreover, when they wish to produce offspring, they go to the East, near Paradise, where there is a tree called the mandrake. The elephant goes there with his mate, who first takes from the tree and then gives a little to her husband. And when he eats it, she seduces him, and immediately conceives” (Book of Beasts, 2020, p. 18).

Bo’s imagination leads him to craft lines about the elephant, which seem to comment directly on the Book of Beasts: “Before the elephant impregnates his mate, he forcefully thrusts his tusks into the earth, unearthing and devouring the potent root of the mandrake!” The ritual of consuming mandrake flowers, which serve as a substitute for the “desire” that elephants, as noted, lack, is also mentioned in the poetic text:

Is life а cinch for heavyweights ?

But both the husband and his mate

(the tower is supported – don’t you gaze?)

Are wandering, both lovers, in a daze,

And chick–to chick –

(the mountains themselves), they’re heading to the secret sierra,

or, rather, clearing in which the woods are dense.

And delving by the stream, the caring signora

Is offering her mate a human mandragora.”

Flaubert’s imagination presents an elephant that challenges the mythological narrative: “A white elephant, draped in a golden mesh covering, comes running, shaking a bunch of ostrich feathers attached to its forehead band. On its back, nestled in cushions of blue wool, sits a woman with crossed legs, half-closed eyelids, and gently nodding her head. She is dressed so dazzlingly that she shines with rays of light. The crowd prostrates itself, as the elephant kneels, allowing the Queen of Sheba to gracefully slide down its shoulder, her radiant presence descending onto the luxurious carpets as she approaches Saint Anthony.” (Flaubert, 1999, p. 52).

The name of the Queen of Sheba is associated in the biblical text with King Solomon, whom she left after acknowledging his wisdom and showering him with gifts. In apocryphal literature, the Queen of Sheba is attributed with having an erotic relationship with King Solomon and bearing him a son. In Arabic literature, there is a source that claims the Queen sent marriage proposals to Solomon, and at the wedding feast, she beheaded him, thus echoing the story of Judith and Holofernes. Further reading of Flaubert’s drama reveals a striking discovery. The description of the Queen of Sheba appearing before Anthony on the elephant matches the description of the courtesan Kuchuk Hanem, who captivated Flaubert during his two-year journey to the East (1849-1851). I’ll start with the description of the Queen of Sheba:

“A dress of gold brocade, trimmed with pearls, agates, and sapphires, evenly spaced, tightens her waist with a narrow corset adorned with colored appliqués depicting the twelve signs of the zodiac. She wears very high boots; one is black, studded with silver stars and a crescent moon, while the other is white, covered in golden specks with the sun in the center. Wide sleeves, edged with emeralds and bird feathers, reveal a small, round hand with an ebony bracelet at the wrist, and her fingers, adorned with rings, have nails so sharp that their tips resemble needles.

A flat gold chain passes under her chin, rises along her cheeks, spirals around her hairstyle dusted with blue powder, then descends to touch her shoulders and is attached to a diamond scorpion, which extends its tongue between her breasts. Two large yellowish pearls weigh down her ears. The edges of her eyelids are painted black. <…> She takes him by the beard. ‘Laugh, O beautiful hermit! Laugh! I am very merry, you will see. I play the lyre, I dance like a bee [italics mine – A.P.], and I know many stories, each more amusing than the last’” (Flaubert, 1999, pp. 52-54).

The drama The Temptation of Saint Anthony, like every work by Flaubert, contains something without which Flaubert could not conceive his writings: “In every work of art, there is something special, inherent to the personality of the artist, that allows the work to either captivate us or provoke us, regardless of its execution” (Flaubert, 1984, p. 199).“Flaubert’s deep personal connection to the work is evident in his confessions: “In Saint Anthony, I myself was Saint Anthony” and, “It was a temptation for me” (Flaubert, 1995).

Flaubert’s confessions lead us to reinterpret the myth of the Queen of Sheba…” who stepped onto the glass floor of the palace built for her by Solomon, lifting her dress high, into Flaubert’s fantasy of meeting Kuchuk Hanem:

“On the staircase, directly in front of us, against the backdrop of the blue sky, stands a woman bathed in light; she is wearing pink shalwars, and the upper part of her body is covered only by a transparent dark purple gauze.[2] She was coming from the bath; her firm breasts smelled of freshness and a sweetish turpentine; she poured rose water over our hands. We climb to the second floor; to the left of the staircase is a lime-washed room: two sofas, two windows, one with a view of the mountains, the other of the city. <…>

Her eyes are black, enormous, with thick black eyebrows, beautifully shaped wide nostrils, strong shoulders, and a lush, round chest. On her head is a fez, crowned with a convex gold disc with a small green stone in the middle, resembling an emerald. <…> Her black curly, unruly locks are parted in the middle and braided into small plaits that converge at the nape of her neck. One of her upper teeth is slightly decayed. On her wrist is a bracelet made of two gold rods twisted around each other. Three rows of hollow gold beads form a necklace. Earrings in the shape of slightly convex gold discs with small gold beads around the circumference. <…>

Kuchuk performs ‘the bee’ for us. <…> While dancing, Kuchuk undresses, leaving only a handkerchief, pretending to cover herself with it, then throws the handkerchief aside. This is ‘the bee.’” [Italics mine – A.P.] <…> After our passionate encounters, she falls asleep snoring, leaving her hand in mine; the faint light of the lamp, barely reaching us, falls on her beautiful forehead in a triangle of bright metal, while her face is shrouded in darkness. <…> I imagined Judith and Holofernes lying next to each other. At a quarter to three—a surge of tenderness upon awakening” (Flaubert, 1999, pp. 92–94).

The impetus for Flaubert’s choice of the elephant as a topic, according to Vyacheslav Ivanov, was an Indian miniature depicting the god Vishnu “on an elephant formed by the interweaving of female figures.” Similarly, Bo could have been inspired by Flaubert, perhaps with a nudge from the Chairman of the Earth’s Sphere, Velimir Khlebnikov, a key figure in Russian Futurism who often drew parallels between himself and the Hindu god Vishnu, embodying a cosmic vision in his work.

“No one will deny…” (V, 115–117), wrote Khlebnikov, even specifying, in a style very much like Bo’s, the exact date (January 26, 1918): “that I invented a new form of illumination. I took Flaubert’s The Temptation of Saint Anthony and read it entirely, lighting one page and reading another by its light: many names, many gods flashed through my mind… and then all these beliefs, venerations, and teachings of the earth turned into black rustling ashes… (remember the remark: ‘The ashes of the gods fall from above’,” (Gasparov 1977, p. 248).

As we can see, the fantastic circle is closed in the symbolism of rings: the Indian miniature, Flaubert—Khlebnikov—Dali—Halsman—Bo—Shemyakin. This symbolic connection weaves through time, linking the works of artists and writers across cultures and eras.

In December 1856–January 1857, Flaubert published several episodes of the new edition of The Temptation in the magazine l’Artiste, whose editor at the time was Théophile Gautier. As for Bo…

“And I sent the manuscript to Shemyakin with the following message:

‘Dear Misha!

<…> I have reached the end of a major work in verse—possibly a book or at least a poem—which I conceived and promised to complete specifically for you. Essentially, it is a gallery of beasts, akin to a medieval bestiary, in which creatures and monsters are presented with fantastical and mythological qualities rather than natural ones.’”

At the same time, it’s a collection of terrifying images that once tempted Saint Anthony, which he triumphantly resisted and overcame. It is precisely the combination of these two well-known European plots (myths, legends?) that is my unique innovation. The rest is merely poetic text, of which you are the judge, in the sense that it envisions fields or even entire pages for your creative flourishes. I may add a few more pages, but those are just details—the book is now complete. Therefore, I am eager to send it to you for your enlightened review, so that good intentions may be matched by deeds.

Sincerely yours, Dmitry Bobyshev.”

Whether there was an immediate response, I don’t remember… Weeks passed—centuries, it felt like—before I could bear it no longer and called Mikhail. As I awaited his response, Mikhail was already deep into his work on the illustrations. But how? He was already in Turin. After all, his illustrations for the volumes of Vysotsky and Yupp were being printed there. The artist’s studio is wherever it’s convenient for him to work. The printing workers appear behind him from time to time. Such moments happen only once in a lifetime. The illustrations are being born before their eyes. “Only in Italy do they know how to print well,” Misha confided to me. I, in turn, received a clarification.

Like Yupp’s books (1986) and Vysotsky’s (1988), Bobyshev’s book was printed on tinted paper, which is incompatible with the ink. I inhaled deeply, as the wind of fortune filled my lungs. No, I could not revel in his glory. But here’s what’s important: finally—the book! The book is coming out soon…” (Bo, 2008).

Footnotes

[1] The word cynocephalus (Greek κυνοκέφαλοι) literally means “dog-headed”, but in its usual meaning this word meant “monkey”, or more precisely “baboon” or “baboon”. So, having encountered this sacred Egyptian animal, the Greeks began to designate it. Interestingly, this name is also enshrined in the modern scientific name of the baboon (Papio cynocephalus ursinus). The first to describe a certain person under this name was Herodotus.

[2] The juxtaposition of pink and violet forms the central image in the ero–text by Nabokov , Flaubert’s diligent student. “The rose garden is an image filled with symbolism, <…> an enclosed rose garden is an allegory of the vulva in the folklore of the most diverse cultures and literary traditions <…> In Kabbalah, the rose is the code of unity and mystery (already in Egyptian culture and Antiquity, mystery is associated with the rose and the enclosed garden, cf. the origin of the concept of sub rosa. <…> Humbert’s first sexual experience in the rose garden thus sets the dual image that is fundamental to the entire novel [Lolita – A.P.], in which the erotic is associated with the mystical. <…> Purple becomes another color leitmotif of love and Lolita (see the similar sound image of her name with the name Lilith). The name of the color comes from lilies, mostly white, and the lily is directly identified with the girl” (Kheteni, 2022, pp. 53-54).

To read other chapter/parts of this series, please click here

About the Author

Asya Pekurovskaya was born in Leningrad, Russia, and after marrying a storyteller and earning a Master’s degree in literature from Leningrad University, she emigrated to America. She completed a doctoral program in literature at Stanford University and has also participated in a post-doctoral seminar in philosophy at the University of Virginia at Charlottesville.