On Raglan Road of an autumn day

I saw her first and knew

That her dark hair would weave a snare

That I might one day rue . . .

(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EuafmLvoJow)

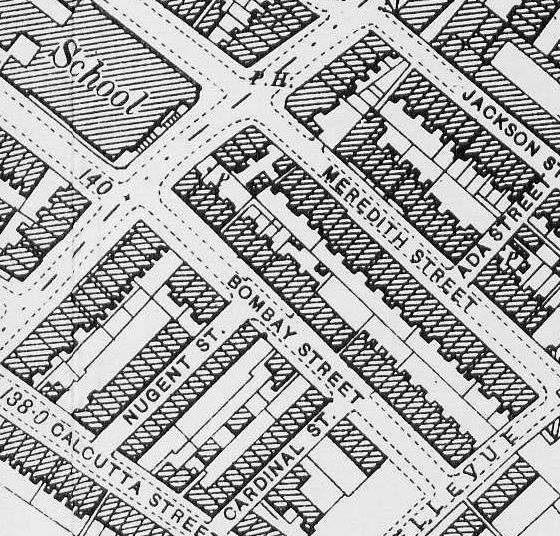

Clonard, is it? Most people would say that the place name derives from Cluain Ard, the ‘high meadow’. It is, of course, Clann Ard, ‘the high family’: high all the time on marijuana they were. The Mukherjees. A decent Indian family, from New Delhi, still fondly remembered today in Clonard – though they had to move (very quickly) to Bombay St. (It was a toss-up between Bombay St. and Calcutta St.)

The Mukherjees, as it happened, only spoke Irish (Gaelic): Mr Mukherjee, Mrs Mukherjee, their wee son, Master Mukherjee and their daughter, weeMiss Mukherjee. (In fact, wee Miss Mukherjee only knew two words of English, ‘F**k off!’, mostly addressed to the notorious Royal Irish Constabulary.)

Bombay St., you say? Ah! Well, that’s obvious, isn’t it? Not as obvious as it may seem, actually. You see, the Mukherjees were only just settling in when they were ‘bombed away’. Alas.

The street was known as ‘Bombed Away St.’ for a while, and eventually shortened to Bombay St.

Bombay (in India) is now known as Mumbai (after Prime Minister Modi’s mother, whom he still fondly refers to as ‘Mum’. Touching.)

Meanwhile, back in Belfast, the true story of how Bombay St. got its name is largely forgotten. Sic transit Gloria Swanson. (Swanson has nothing to do with our cautionary tale, though you may be interested to know that she was a follower of the yoga guru Indra Devi, but let’s not go there! Please.)

An Indian student at Queen’s University, Maaz Bin Bilal, investigated the whole sad history of Bombay St. and the unfortunate Mukherjees. He even wrote a stirring poem about it and sent it off to The Honest Ulsterman. They wrote back to him, after two years, saying, ‘We don’t publish fantasy!’ So, Maaz submitted it to Modern Literature (Chennai) and, lo and behold, it was published the following day, to universal acclaim!

(from The Honest Ulsterman)

Place names are notorious, in all parts of Ireland, not least in Belfast; they often lead to heated debate, even skirmishes. Two unrelated families, the Malones, fought for years as to which branch of the family Malone Road in Belfast was named after, until eventually an academic from Cork was called in to conclusively prove that Malone Rd. has absolutely nothing whatsoever to do with any Malone, living or dead. Both branches of the Malone family attended and listened dutifully to the first few minutes of his two-and-a-half-hour tirade on the subject.

‘The surname Malone derives from ‘maol’ meaning ‘bald’ or ‘tonsured’, or ‘a servant’ – and the second syllable, ‘Eoin’, means ‘John’. You know all that already, I’m sure. However, that does not mean that Malone Rd. derives from someone of that name. No. Not at all.’ The Professor shook his head, for emphasis, showering his shoulders with a fine coating of dandruff.

The Malones were pulling their hair out even before the Professor got into his stride. He took a glass of sparkling water, glanced anxiously around the room, feeling the mounting tension.

A stranger in the city, from the southern outpost of Cork, he had no way of distinguishing the two main branches of the Malone sept who were seated threateningly in front of him, one to the left, the other to the right, the ‘lefties’ seated to the right, as it happened, and the reputed right-wingers on his left. (In fact – though the Professor could not have known this – some Catholic Malones were seated next to some Protestant Malones, united by left-wing working class politics.)

‘I know that you Malones are a proud people,’ said the professor, feeling that he needed their support. ‘Annie Malone did a lot to straighten out African-American hair, as you well know and . . .’ This was greeted with a blank stare. The professor laughed nervously, looked at his notes, and continued, bravely:

‘The Malones! You’ve been everywhere, done everything. From Bishop Richard J. Malone to porno star Roberto Malone!’

Silence. A woman stood up and left.

The professor continued, unfazed. She wasn’t the first woman to abandon him. (But that’s a story for another day):

‘There was a Séamas Ó Maoileoin, God rest him, who fought tirelessly for the Irish language. He almost came to blows with a priest who refused to baptise a child because it had a Gaelic name! Those were dark days. Are they any better now, I wonder? Séamas may not be known to you but many of you here today must have known another stalwart, Brian Ó Maoileoin and his very talented family. If memory serves me well, Brian had a play performed on Tory Island – the same couldn’t be said of Patrick Kavanagh!’

Another person stood up, gave the professor a withering look, and walked out.

The professor dispensed with his notes – swearing silently to himself that he would never again use Wikipedia – and threw himself into his subject forthwith by saying that Malone – in Malone Road – means, simply, ‘the plain of lambs’. He conceded, nonetheless, that the second part of the name could also mean ‘a fat calf’. He even went so far as to suggest ‘a kid goat.’

The Malones were too busy shooting daggers at one another to lambast the professor when he uttered those sissy words, ‘the plain of lambs’. When they started paying attention again, the professor was well into his stride.

‘Of course’, he intoned with the confidence of someone who has been over this ground a thousand times before: ‘the second syllable could also be a corruption of leamhan, namely ‘the elm tree’. Could it not? Or leon, a ‘lion’, figuratively ‘a warrior’.

By the time he had got to‘a haunch-like hill’, the Malones – both branches – were nearly fit to kill him – and each other. ‘Haunch, or hip, or buttock . . .’ on and on the Professor droned until, one by one, the Malones rose and without nodding to the learned man on the podium, trudged home, dejected, too dispirited to fight out their differences or argue any further.

There was only one man standing at the end of this tortuous lecture, a man from Donegall St – not a Malone himself, or related to any Malone, simply someone who turned up at the talk because he was lonely, in desperate need of the odour of packed humanity. He very politely asked the Professor if he knew anything at all about his own beloved area, Donegall St., particularly its reputed dampness. As luck would have it, dampness – particularly in the Donegall St. environs – was one of the Professor’s areas of research.

‘Yes, my good man, ‘he replied, jauntily. ‘As far back as 1801, that very area was known far and near for its dampness. A gravelled footpath was constructed for the health of the soldiers. If memory serves me well, the reasoning behind it was as follows: dry feet are of the utmost importance and wet ones a most fertile cause of disease for armies.’

‘That calls for a drink,’ exclaimed the man from Donegall St.

‘Where’s the nearest watering hole?’ asked the Professor, anxiously.

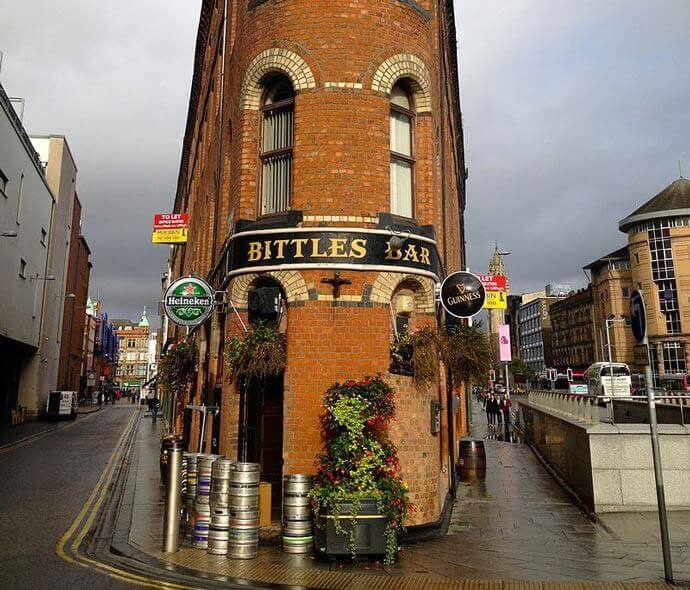

‘Bittles,’ said the other, a little spittle dribbling from the corner of his mouth.

Later, in Bittles, the Professor noted several portraits of Irish writers on the walls – James Joyce, Oscar Wilde, W B Yeats, Samuel Beckett et al: at least the obnoxious Kavanagh wasn’t among them – not in his line of vision at any rate –which came as a great relief to him.

‘The usual suspects, I see,’ the Professor observed wryly to his companion. ‘No Irish-language writers allowed, it would seem.’ The man from Donegall St., knowing nothing at all about literature – in any language – quickly brought the topic back again to Belfast place names.

‘Take Raglan St.,’ said the Professor.

‘You can have it!’ said the other.

‘Well, of course, everyone thinks it’s called after Raglan, commander of the British forces during the farcical Crimean campaign against Russia. That may be true of Raglan Road in dirty old Dublin, subject of a mawkish song by that Kavanagh buffoon. The Queen of Hearts still making tarts! I mean to say, what kind of nonsense is that? Does he take us all for fools and clodhoppers?’

The other man nodded in agreement, though he had never heard of Kavanagh, or his mawkish song.

‘Kavanagh! Ah, well, sic transit Gloria Guinness,’ sighed the Professor.

‘You’ll have a Guinness?’

Raglan

‘No no! Whiskey is fine. Where was I? Oh yes, well, before any Crimean campaign, the locals – in the area now called Raglan St., here in Belfast – the locals were fond of a bit of raglin’, as they called it.’

‘Raglin’?’ exclaimed the Donegall St. man. ‘And what might that be? Sheep stealing?’

‘Ah,’ says the professor, thoughtfully. ‘That too! And more. No, I was thinking of what we’re doin’ now.’

He looked out at the lowering skies. The other followed his gaze.

‘From the Irish, my good man, rag, or raga – not to be confused with the Indian raga, the six musical modes – no, the Irish rag means the season of short days and long nights, during which a man might find himself inclined to ‘ragairne’ or late-night imbibing. Order another wee Bushmills there like a good man.’

‘Will I make it a wee double?’

‘Sure we might as well be hung for a sheep as for a Malone.’

Returning with the drinks, the Donegall St. man composed himself and said, rather sheepishly, ‘Beggin’ your pardon, Professor, but it’s not a word that’s used in these parts at all.’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘Raglin’, Professor.’

‘No, of course not. It’s gone.’

‘Where did it go?’

The Professor sighed: ‘Too much raglin’ leads to forgetfulness, my good man.’

Someone started to sing. Such a look of incredulity on the professor’s face the other man had not seen in all his born days.

‘It can’t be,’ the professor muttered darkly. ‘What have I done to deserve this?’

The singer had already commenced on the second verse of Raglan Road:

I saw the danger, and I passed

Along the enchanted way

And I said, “Let grief be a falling leaf

At the dawning of the day . . . “

About the Author

Gabriel Rosenstock is a bilingual poet (in Irish & English), haikuist, tankaist, playwright, novelist, short story writer, essayist, translator, writer for children and champion of ‘forlorn causes’ – the phrase is Hugh MacDiarmid’s. He is a Lineage Holder of Celtic Buddhism and a member of Aosdána (the Irish academy of arts and letters). Among his awards is the Tamgha-i-Khidmat medal (Pakistan) for services to literature. His latest titles are free volumes of ekphrastictanka, Every Night I Send You Flowers, and The Road to Corrymore, published by Cross-Cultural Communications, New York, and EDOCR: https://www.edocr.com/v/ox5ekdgm/gabrielrosenstockbis99/EVERY-NIGHT-I-SEND-YOU-FLOWERS

His website: https://www.rosenstockandrosenstock.com