Interview by Ahmed Amor Zaabar

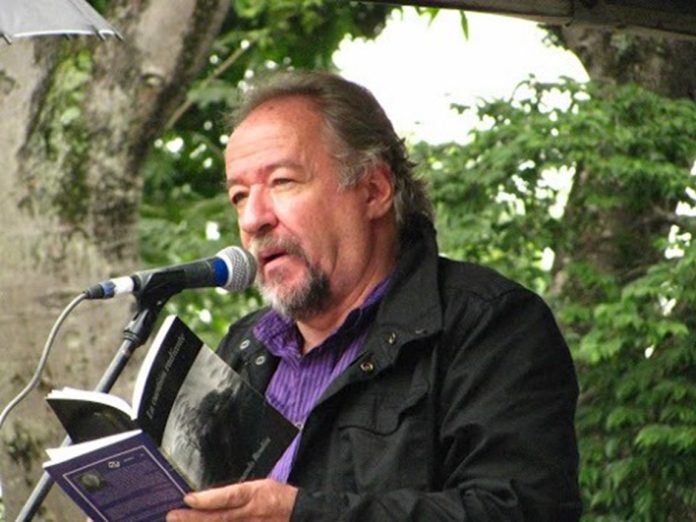

Fernando Rendón is one of Colombia’s most influential poets and the visionary founder of the Medellín International Poetry Festival, a celebration that has transformed his city into a global hub for poetry. Over the years, Rendón has not only carved out a remarkable literary career but has also used poetry as a tool to confront social, political, and cultural challenges in Colombia. In this interview, he reflects on his journey as a poet, the evolution of the festival, and the profound intersection between art & politics in his life and work.

Identity, Beginnings, and Becoming a Poet

Ahmed Amor Zaabar – You are known as both a poet and the founder of the Medellín International Poetry Festival. How do you define yourself today, and what does it truly mean for Fernando Rendón to be a poet?

Fernando Rendon – While poetry seems indefinable, some poets attempt to define it in different ways. Unable to define everything, even if it hurts our reasoning, we can only clarify various aspects of existence. Everything in the world is changing and relative. Allied with the power and spirit of poetry, we can contribute to changing the reality of our time. The impact of poetic action is intangible. Everything changes every moment. Poetry is a form of knowledge and transformation of individuals and peoples. To be a poet is to develop and express a renewed and renewing thought, vision, and perception while being part of a single body of existence. The poet embodies and manifests the dream of an alternate life.

AAZ – Can you tell us about your childhood and early life? What were the first moments that led you toward poetry, and when did you feel it was not just an interest, but a destiny?

FR – My childhood was happy, imaginative, and cheerful. Poetry was involved in our games. However, life in the classroom was the expression of a brutal dogma that I resisted, a dogma that opposed the constant search for truth in mutation and transformation. The struggle against dogma and rigidity continues today in my life and in the lives of millions of people. There is no absolute truth. I was introduced to poetry through my father’s poet friends and through contact with the poetic experience and books of poems. In my adolescence, poetry became a new way of living, of understanding existence, and of transforming my perception. And a destiny.

AAZ – Has poetry changed you as a human being over the years? If so, how?

FR – Poetry has changed me. It has given me the courage to face life and death. It has shown me that our dreams can come true, even if it costs us our lives. Poetry has led me on the roads of the world, and I have seen and experienced its power. I have nourished my life with the readings of essential poets. But I have also learned from poems and contemplation that life is experience and an ocean of energy that flows through us, constantly renewing itself and circulating wherever it wants.

Medellín, Place, and Historical Context

AAZ – Medellín has a complex and often painful history. How has living and writing in this city shaped your poetic voice and your vision of the world?

FR – Medellín was a peaceful city many years ago. But the constant armed conflicts in the country and their aftermath left a legacy of accumulated social decay. The evil experiment of turning sacred plants into chemical drugs brought destruction and death to Colombia. Drug trafficking sparked a new war and led to the deaths of 45,000 people in Medellín between 1990 and 2000. My poems were influenced by that tragedy, and my friends and I acted forcefully against the killing, show a path to peace, and try to change the spiritual climate of the city.

AAZ – What does it mean to write poetry in a country marked by violence, inequality, and social wounds?

FR – Writing poetry against violence in Colombia’s history means living and fighting against death. Poetry is a powerful medicine against hatred. Without poetry, it is impossible to heal the wounds of war and move forward in creating a peaceful atmosphere of reconciliation and reconstruction in the country, even if these processes take time. Antagonisms are obsessive and pathological. Social ills are very old and take centuries to heal.

The Medellín International Poetry Festival: Origins and Evolution

AAZ – How was the idea of founding the Medellín International Poetry Festival born? What were the motivations behind it?

FR – By 1991, Medellín had become a crime capital. Both the Colombian state and the mafia were terrorist entities. The state ordered the physical elimination of 6,000 leaders and militants of the leftist opposition. For its part, the mafia arranged for the execution of hundreds of police officers, putting a price on their heads. Revolutionary guerrillas fought against the Colombian army and a considerable paramilitary force (drug gangs). Being a hitman was a lucrative profession. Bombs were a daily occurrence. Because of this, the streets of cities, especially in Medellín, remained empty. Anyone could be killed at any time. Gatherings of more than three people were prohibited. We were all under threat. To oppose the absolute reality of death, to confront the unlimited killing, we founded the Medellín International Poetry Festival.

AAZ – What were the main challenges in the early years of the festival, and were there moments when you felt it might not survive? What kept it alive?

FR – The biggest challenge was to ward off fear, to make beauty dissolve the panic in the streets. Another complex challenge that has a manifestation of poetic resistance is the financial one. Since poetry does not produce material profits, there is no money for poetry in the world. In the beginning, we made calls from public phone booths, and all our organizational work was voluntary. But during the first ten years of the festival’s existence, which were the most violent years in the life of Medellín, the greatest challenge was to stay alive, alert, and active. As the French poet Yves Bonnefoy wrote, “in Medellín the Festival took place on the frontiers of evil”. We endured threats, pressure, and deprivation. And of course we were afraid of death. But our fear of inertia and inaction was greater. Our love of life prevailed, as did our confidence in poetry as a manifestation of the spiritual battle of the people of Medellín.

AAZ – How has the festival changed from its beginnings to what it is today, both artistically and socially?

FR – The Festival went through many difficult trials and crises, and has survived, like us, for more than a third of a century, experiencing most forms of death and life, maturing in its poetic concept and artistic quality. Although we wanted to bring in the greatest contemporary poets, not all of them came. Wole Soyinka, Saadi Youssef, Abdellatif Laabi, Ko Un, Eduardo Sanguineti, Andrei Vosnesenski, Blanca Varela, Juan Gelman, and Mazisi Kunene were among more than two thousand poets from 197 nations. Some of those who did not come participated virtually, such as Adonis, Antonio Gamoneda, Charles Simic, Paul Muldoon (who will come in 2026), Roger McGough, Anne Carlson, and Adam Zagajewski. We tried to be careful in selecting the guests. With the pandemic, the audience decreased, but it is gradually returning. The festival remains strong and alive, with a large audience. The wind of poetry continues to blow over the city.

AAZ – How do you see the future of the Medellín International Poetry Festival?

FR – The political situation in the country has gradually improved. A progressive political force now predominates, bringing about political, economic, and social changes, with a relatively stable outlook, despite the expected opposition from the right, which uses all kinds of tricks and slander to discredit the rising force for good. We hope that these changes will also extend to the cultural sphere and that poetry will be understood as a force capable of sustaining transformation. If this happens, we can look forward to a better future for Colombia and for the festival. Otherwise, we will continue to fight as we always have so that poetry can manifest itself in Medellín and everywhere else, strong and active.

Politics, Power, and Resistance

AAZ – Colombia’s political history is deeply turbulent. How has politics affected the festival over the years, including censorship, pressure,and hostility?

FR – As in many countries, poetry is required to be apolitical, and poets are not allowed to express critical thoughts about reality. This in itself is an expression of censorship. The festival has suffered constant accusations because of its free spirit, it is persecuted by an inquisitive gaze, and it is subjected to intimidation, slander, and threats. When politics becomes so involved with the festival, we are Pushed to express ourselves politically. The festival is a bastion of freedom of thought and expression. Life cannot grow in captivity. Poetry exists and cannot cease to be. This is its dignity, When a country and a people identify with such a spirit, over time they will become unyielding. Poetry nourishes the spirit of freedom in all times, keeping it safe and intact.

AAZ – In recent years, there have been attempts by local authorities to interfere with or stop the festival. Can you describe what happened and how these political and bureaucratic challenges affect the festival’s work and its relationship with the community?

FR – The festival has suffered numerous cuts in national and local funding, including a total financial blockade by five city mayors. Six years ago, the Ministry of Culture denied its financial support to the festival. As a result, it seemed on the verge of disappearing. We developed an international campaign to collect signatures and promoted visits and messages from foreign poets to Colombian embassies abroad. The large number of letters sent to the minister overwhelmed her email. Finally, the national government had to reconsider its hostile decision.

In the recent crisis caused by a local right-wing politician who wanted to repeal the law that allocates an annual budget for the Festival, we received 500 letters of support from poets in 150 countries, which was a strong show of support and a source of peace and joy for us, a respite from the constant threat and a new temporary victory against the eternal adversaries of poetry and life.

AAZ – What does it mean for you and for the poetry community in Medellín to keep the festival alive despite these attempts to hinder it?

FR – Having held the festival for 35 years, its continuity constitutes a symbol of resistance of the spirit from a shore that was unthinkable in another era. The expansion of poetry in the world is more necessary now than ever; poetry expresses independent and creative thinking about reality, which has become more obscured with the inevitable fall of the empire and Zionism. In the messages we have received from so many countries on all continents, there is a perceived identity and agreement that the festival, as a pillar of world poetry, must remain vital and active, and we are taking all measures to ensure that this is the case and to contribute to poetry remaining the centre and symbol of human hope that does not yield or surrender.

Poetry and Politics: A Personal and Ethical Question

AAZ – How do you personally navigate the relationship between poetry and politics? Do you believe poetry should take a political stance, or remain free from ideology?

FR – Right-wing politics and ideology have abruptly imposed themselves on the world and cannot be ignored. Just as poets must show solidarity with Gaza, it is essential to reject the aggressive presence of US ships, planes, and troops off the coast of Venezuela. The invasions of Gaza and Venezuela are both acts of imposition and violence by very dangerous forces. All manifestations of aggression against life in any country constitute attacks on humanity, and we must oppose them by demanding peace and respect for peoples. Everyone’s live is at stake. However, our position must be expressed through the language and actions of poetry. The dream of human spring is a poetic dream, not a political slogan. Poetry unifies human beings above their differences of thought. It is not thought that associates. It is the heart that fuses.

AAZ – Do you see poetry as a form of resistance? If so, what kind of resistance?

FR – Poetry resists the eternal destruction of beings and the social forms of death. Resistance is the preservation of liberating language and the living memory of ancestors. Resistance is the unity of poets and constant poetic action in defence of life. We resist devastation by celebrating existence. Resistance must lead to a global poetic revolution as a state of spiritual transformation that leads the species to achieve peace, justice, and harmony and to avoid catastrophe.

AAZ – How do you define the responsibility of the poet toward society?

FR – Poets cannot change society, but they can support the struggle of peoples who resist oppression and transform the world. Poetry is the voice of the people, the art and dream of transformation. The poet embodies the imagination of new life.

Poetic Practice and Inner World

AAZ – In your own poetry, how do you balance the personal, the lyrical, and the political?

FR – I don’t seek to balance them. Balance comes naturally. Personal, emotional or political issues arise every day, and we respond to them in their own time with persistence and dedication. Life and poetry are affected by the reality of human history. We oppose this with our energy and our poems. It couldn’t be any other way. I know of no more beautiful response to political oppression than poetry.

AAZ – What themes recur most frequently in your poetry?

FR – The daily nuclear threat, the attempt to crush the will of peoples through inhuman fascist wars, the inevitability of going through all forms of death and life always bring me back to thinking about the immortality of peoples and cultural heroes throughout the centuries. I am obsessed with the permanence of human life on earth despite uncertainty.

AAZ – What role do hope and solidarity play in your poetry and in the festival as a global poetic space?

FR – In 2011, we founded the World Poetry Movement in Medellín as an expression of the will and hope of poetry in the victory of life over the dark forces of destruction. In the Movement, based on the solidarity and hope contained in the nature of poetry, poets from all regions of the Earth express themselves. In 14 years, the Movement has developed 23 global poetic actions, including several in defence of Gaza.

Poetry Today and Advice for the Future

AAZ – In a world increasingly dominated by speed, noise, and distraction, what is the place of poetry today?

FR – Poetry occupies a vital place in the life of youth of the world. The poet is a paradigm in many countries. Festivals, virtual and printed publications, schools, and poetry workshops are being founded everywhere. It is about believing and trusting in existence, writing and fighting with the passion to create new revolutionary forms of life. The immortality of the dream is made of powerful fibers. Poetry multiplies in daily encounters, in networks, in the arts, discovering new paths. Poetry closes all roads to dejection.

AAZ – What advice would you give to young poets in Colombia and around the world?

FR – Read the great poets, engage with their poems, seek out the paths of poetry to its very core, and write everything down. Instead of competing, unite to embrace and protect the miracle of existence. Carry in your hearts the world and defend it. Achieve the impossible, which is the only thing worth fighting for. Triumph together against the enemies of life.

AAZ – After so many years of poetry and cultural struggle, what keeps you writing?

FR – What keeps me breathing and fighting keeps me writing, the love of life in the place where we remain united with all those who breathe and fight for the victory of light.

Fernando Rendón is a Colombian poet and cultural activist, best known as the founder and director of the Medellín International Poetry Festival. Born in Medellín, he has been a leading voice in using poetry as a form of social resistance and collective healing in Colombia. He is the author of several poetry collections, including Contrahistoria, Bajo otros soles, and Los motivos del salmón, and his poems and essays have been widely published and translated. Rendón is also a co-founder of the World Poetry Movement, through which he continues to promote poetry as a force for peace, freedom, and human dignity worldwide.

About the Interviewer

Ahmed Amor Zaabar (Tunisian, living in London) is a poet, writer, and media specialist. He is the former Chairman of the Cultural Committee of the Arab Cultural Forum in Britain, the former Chairman of the Media Committee of the Arab Club in Britain, and the Vice President of the White Ink Club in London. He has published three poetry volumes, and is currently working on 3 new poetry collections. His poetry has been translated into French, Spanish, Chinese, Italian, Serbian and English. He has been featured in numerous poetry anthologies and has participated in several international poetry festivals