Translated from the Tamil by Thangeswaran

I got off the bus, and stepped out of the exit door looking up at the road across and the row of shops on the opposite side. I could not recognise the town where I had lived twenty-five years ago. The buildings that had grown to the sky hid the old signs of this town. I could not see the branches of the trees that touched the sky, nor the squirrels that had run and played over them. The sky was fully covered with clouds, so I had trouble judging the directions to walk further. When I turned to the left, the blue peaks of the Western mountain range stood tall helping me identify the western direction.

Yes! It was the west. When I lived here as a child, whenever I stood at the door of my hut and looked west, the mountain stood majestically. Rather than watching the sunrise and knowing the East, the western mountain helped everyone to know the directions. As far as this town is concerned, it is easier to identify the East after getting to know the West by looking at the mountain ranges. When I realized that the situation remained the same even today, the scent of my town’s soil entered my nostrils.

The all-around green of the thick forestry and the fresh wafts of breeze from the greeneries are the specialities of this home town of mine. Even into a weak nose, the green breath entered automatically and snorted like a puppy. I don’t know if that atmosphere can be seen today. Perhaps it looks concrete jungles and all around artificiality as I am now walking through the centre of the town. Probably, the green nature is still found a little away from the town centre.

I crossed the busy road quickly and walked in the opposite direction. At the entrance of a shop, a middle-aged woman was selling small bundles of various varieties of green spinach. Mahila and Kumutti variety spinach were the mainstays. On one side, bunches of drumstick leaves, and on the other, coriander leaves were scattered as separate small bundles for sale.

Those days in the past, my mother and I gathered whatever we could find growing in the gardens and forests, without asking for permission or waiting for the right season. We salted and boiled the greens, herbs and vegetables we collected, and then we ate them. Today, such products of nature that were available free, have become commercial goods of value and often, not affordable to the common men. The days when money was not the primary concern are long gone; what nature once offered for free to the poor has now turned into commercial products.

Many young people come to buy spinach. That is really surprising. in the past, it was the women’s job to go to the market and buy spinach and vegetables for the household. Today, I did not see a single woman buying spinach here. It seems that the days when everything, from buying groceries to lighting the stove, was assigned to women are largely gone nowadays. From waking up at four in the morning to going to bed at eleven at night, they used to be busy with household work. Besides gardening and housekeeping, they were fully engaged in agricultural work. Those works were automatically assigned to women, and the women too took them up without any grudges, accepting that those tasks were the responsibilities of women. My mother also lived like that.

With many people rushing to buy the fresh spinach and the vegetables, the stocks sold out quickly. The vegetable grocer put together the morning’s collection of coins, ten- and twenty-rupee notes and place the cash her shrunken purse. The sale price of spinach and small lots of vegetables used to be in ten and twenty paise in the past and now is in full currency notes like ten and twenty rupees.

After the sale of spinach was over in half an hour, she took a broom, collected the scattered leaves that had been spilled here and there, cleaned them, and then fetched water from the tap inside the bus stand and cleaned up the floor. The shop owner was now not required to pay separate wages to his staff for cleaning and washing the area in front of his shop. This meant that his profit goes up with this cash saving.

As I moved further towards the east, I observed many more women engaged in diligently sweeping and cleaning each shop. Each woman took care the maintenance of at least five shops, thereby earning a monthly wage for her efforts, though very minimal amount, and this has been the legacy of a long-standing practice.

The Maathaari women, particularly from the local community, took charge of cleaning commission-traders’ shops, and they were fairly compensated for their work. Additionally, they often had to yield to the personal favours sought by the shop owners, and at times received a small additional monetary compensation for the same. An additional layer of exploitation by the shop owners!

Fair skinned women commanded special respect in this profession and asserted their authority over their other less-fortunate women colleagues and often bossed over them. While shop owners may feign ignorance of these dynamics, they secretly grant these women certain privileges as a recognition of the importance of the personal secret dynamics.

A young woman was busy drawing a kolam at the entrance of a large textile company after cleaning the ground and sprinkling of water over the cleaned up soil. I could immediately recognize the face of the fair-complexioned Chinnathai in the glowing eyes of that young woman. I stood still for a few minutes and admired the beauty of her kolam. It was a 21-dot kolam. Eight dots stood in all eight directions. Each dot held a lotus flower. The petals of the lotus spread and smiled like the blossoms of her face. She then sat on ground, next to the kolam’s flowers and applied colour powders in the various designs inside the kolam.

After finishing the kolam, she stood up, broke her laziness, and approached me and asked : “who are you, why are you staring at me?”

“You are Chinnathai’s daughter, aren’t you?”

She put down the kolam powder can and looked at my face intently.

“Do you know my mother?”

“I very well knew your mother when she worked as a cleaner at the Seerangam Mothalali’s shop. I used to be addresses on the sacks there.”

“Oh God! My mother’s friend? It’s been five years since she died.”

“Are you doing the same work your mother did?”

“It was my mother who induced me into this job, saying that if I “adjusted” with the shop owner a little, I would earn more than what the regular salaried staff earn.”

The girl continued:

“She didn’t even think of coming up and growing in life. She was selfish and thought of herself only. She didn’t even think of her children. We were being a nuisance at her feet. If I had studied, I would have gone to school or an office. But she did not allow me to study and forced me to a life of menial work like this.”

“I have been wandering around here as I had to follow her footsteps. The owner is a wicked man; his son is too cruel to be spoken of. My condition here has become like the bough of a tree that dances to the wind.”

As she said the above, she took the small tin of kolam powder and went down into the basement of the shop. It might have been the owner’s son most probably waiting there so far; he put his hand on her shoulder and led her intoa cave-like room in the basement.

I let out a sigh and walked up to KTK Mill, carrying my bag. The trees and the wooden box shops had disappeared from the street. A tea vendor, who lived under a tree, made a living by running a tea shop. Not only tea, but also various kinds of food items and snacks, such as vadas and masala kizhanghu would fill the lead trays. The masala kizhanghu from his shop was famous throughout the small town. The big house owners of Upper and Edamal Streets would ask their servants to buy it for them and eat it. The masala kizhanghu cooked with potatoes would smell so good that the smell would reach the inner layers of the brain immediately.

Once, when there was a severe shortage of potatoes, he bought kappa instead of potatoes and made a kappa masala dish. That too was delicious. When the price of potatoes fell, he prepared both dishes, masala kizhanghu and kappa masala. Since the price of kappai was cheap, the lower-class people preferred kappai. While the potato was soft and delicate, the kappa required a little more effort to chew and eat, but nevertheless both the dishes were tasty.

Although everyone wanted to eat the potato based dish, the desires were curtailed by monetary considerations. Those who could not afford to make gravy at home would buy and cook masala potatoes. At noon, KTK mill workers would get a small amount of masala potatoes to eat. My mother, who had been harvesting cotton at the mill, would eat half of it for lunch and then wrap the rest into a small parcel and bring it to me for dinner. Sometimes she would even give it to my father. She would say, “It smells good.” Those nights were a really happy time for my mother and father.

The petty shop that stood majestically facing the north was gone. That shop, which looked like a heart in the middle of the town, has now disappeared. Even a small wound can leave a scar on the body for a long time after it heals. But the petty shop, made of a large wooden box and known to everyone as a throbbing place full of energy like a beating heart, disappeared from the street long ago, and the large tamarind tree that had provided shade for it has also been removed.

The small clean water canal that ran alongside the petty shop has now become a sewer and had a pungent stench. A few poverty-struck families lived on the currently filthy banks of that canal. One family had a man, woman and two children. One of the children sat up, grabbed her mother’s saree collar, and cried. She hit the child on the head and said, “You keep silent, pakki.”

The baby cried even louder. She tried to pull it to her lap and pat its back to make it sleep but failed. “What are you doing, beating the little one?” said her husband.

“This is senseless buffalo; give it your chest nipples for sucking throughout the night. Then only you will feel the pain that I am constantly forced to bear.”

“What a woman you are! Not allowing me to touch you nor permitting the child to suck milk.”

“Don’t you know about me? If I give you a nice kick (your cone will burst), your hip will break into pieces, remember.”

“Go to hell, you devil, you and your ugly child. Keep this to yourself.“ Saying this, she threw the child away.

He said, “vaada kannu” (come, my dear) and put the child on his shoulder and walked towards the east. He bought some milk from a tea shop at KDK Mill’s gate, warmed it a little, and fed it to the child. The child opened his mouth wide and smiled. He looked at the shopkeeper and said, “please write the charges for the milk in my account,brother.” The shopkeeper took out a note, wrote a debit, and said, “The account balance is rising every day; you settle the debt quickly.” In reply the father said, ‘today is Friday. There will be more collections today and I will pay off my debt to you without the balance of a single paisa by tomorrow.” He bought two more sweet suyyams , tied them around his lap, and came to his wife. His daily livelihood profession comprised of dressing up as Lord Rama during the day, and going from shop to shop begging and at night, become a fortune-teller, with a dressed up buffalo tagging along him. He did not get money from people like the good old days, when people used to drop coins and small value notes on hearing his fortune telling. The crowd that believed in the word of God had decreased.

I looked up at the T K Mill. I couldn’t see the majestic compound wall. Parts of the wall had been demolished, and shops had been built. I could tell that the well behind the shops was still there. The well water was supplied to the outside shops. It seems that the mill owner himself had built shops and rented them out. That’s why his well water was supplied to the tenants.

When I saw the tea shop, I felt thirsty. I went to the shop, entered, sat on a stool, and ate a medhu vada and drank a cup of tea. Although it was a small shop, the shop owner gave me a computerized bill, wich surprised me. The world has changed a lot. Computers and smart phones have become very common place, with everyone being able to afford the same. I ventured to ask the shop owner, “enna thambi (brother!), by any chance do you know the whereabouts of a person called Thonthi Chettiar who ran a small shop here?”.

He took the money from me and put it in the kallapetti (cash box) and asked me, “in what way are you related to him?”. He seemed both a like a worker and the boss.

“When I was young, I used to buy and eat spicy food from his small shop; that smell still lingers in my heart.”

“Oh. Is that so. It’s been twenty-five years since he left the village; the village has changed beyond recognition.”

The shop owner further continued:

“I am his son; he lived on the sidewalks of the town like a nomad; I now live in a small house; that is the only development. That’s how our business is going on.”

“Okay, I said, “Will I get that food now, the same old menu?”

“Now all that stuff no one likes or wishes to eat. If you want a few items from the old menu items of those days, you have vada and murukku (a kind of dish made out of flour), but nowadays people don’t like murukku. The sweet and spicy foods are going well.”

The man who used to have his small business on a platform has now reasonably grown to own a shop of his own. I continued walking, greeting him in my mind. I want to see Chinnakamu. Where is she? My mind told me that she is still alive.

She loved me very much. She displayed her love for me even though her father and her mother knew it and did not approve of the same. What’s more, she showered her kisses on me, without them knowing. That kiss was not on the cheek; it was on the lips. Her red lips were always sweet. After she hid inside her house, I suffered from not being able to enjoy her kisses. I lay in penance at her doorstep. She would peek through the door. Her mother scolded me. “Why are you lying here always?”

“Chinnakamu!”

“Now she has become a big kaamu; hereafter, you should not have anything to do with her”

I couldn’t accept that Chinnakamu was called a big kamu. How could the same body that I saw yesterday and last year be a big kamu? She was only allowed to leave the house when her marriage was finalized.. On the day before her wedding day, she came to me and said, “Shall we elope somewhere?” I hugged her with tears in my eyes. She exchanged hundreds of kisses. She pronounced the names of the organs of myself and herself. When I held her breasts and tasted them, her mother saw it. She grabbed the girl and dragged her away, shouting, “You are the worst prostitute.” After a while, her father brought a long stick and hit me on the head. The pain was so intense that it set fire to my brain. I couldn’t bear it. He told my mother with rage that he was going to kill me. My parents were afraid! They took me out of town and sent me to my sister’s house in Tiruppur.

“I kept crying all day long. I cried and cried until my eyes were swollen. I walked to the Noyyal river, sat on its bank, and lamented until dark. I hoped that Chinnakamu would somehow come to know my whereabouts. But it didn’t work out. Time tried to erase her memories. I made Chinnakamu’s memories my clothes and started living as an employee of a garment manufacturing company. After that, I never came to this town. When I worked in the company and earned money, and reached a good position in life, my parents also settled there and started living together with me. My married life consisted of the landscape waiting for Chinnakamu.

I came back to this town to find out how Chinnakamu was doing; I got time only now as the garment manufacturing units were kind of economically paralyzed and stopped their production temporarily due to the increase in yarn prices.

Kaamu was the only daughter of her parents. They got her married to a groom who stayed at her house so that she would stay with them without leaving to her in-laws’ house. She would have passed her life in my memory. So she must be here only, somewhere nearby where her house stood. My eyes wandered in search of her house.

The nearby well with sweet water and the Muthumari temple adjacent to it were still there. The compound wall had been raised, and the temple had grown in size with a tower. Not only was the well in ruins, but garbage had been dumped, and it was filled with dung and ash, and smelled bad. The temple looked like a waxing crescent moon, and the well looked like a waning crescent moon.

Standing at the edge of the decay, I looked at her house. What used to be a thatched hut had been converted into a moderate house with a brick building, and the entrance was paved with paver block stones. Tulsi and Oma plants were growing in flower pots and were blushing with their greenish beauty. Those days, the Vavarakachchi tree, which had grown small now, was not there. It seemed that they had cut the tree down just as they had cut my love down.

I stood on the opposite side of the road, looking out at Kamu’s house. A young woman with the same complexion and face as Chinnakamu came and filled up a plastic bucket with water and watered the plants.

I thought about going closer and asking. I went and asked her : “where is your mother, the green-leafed lady?”

“The memories of her lover, like the sun, have burnt her black.”

“It doesn’t matter if she was burnt black; where is that rare plant now?”

“Time has abducted that rare plant. Look at the sky; she is wandering around in search of her lover.”

I took out a handkerchief from my pant’s pocket and wiped my eyes. A motorbike came very close as if to hit me. But within a second, it went away from me by a thin distance.

“Fool, won’t you stand aside, scoundrel?”

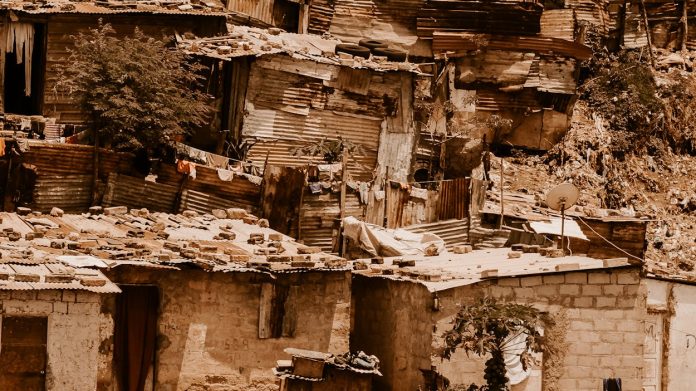

I walked further, carrying my memories. The area where cats, wild dogs, foxes, and wolves lived was now occupied by humans. The plants kiluvai (a kind of small tree, used for fencing) and pothakallis (a thorny plant) which were in abundance long back, had been destroyed, and the forest looked like a bald head. The large puddle of clean water that used to be there was now a sewage drain! The stench wafted to the road. It was on the banks of that stanching puddle that huts housing humans exist now. While the huts inside the town have grown into big modern houses, the huts that had sprung up on the outskirts were now submerged in sewage sludge.

(Note: Original Tamil story titled ஒதுக்கங்கள்! )

About the Author

Theni Seerudayan is a writer from Theni, Tamil Nadu, known for his Tamil short stories and novels. He has authored works like “Nirangalin Ulagam” (The World of Colors), “Otrrai Vasam” (Single Fragrance), and others. His writings often explore themes of social issues, particularly those concerning the visually impaired and marginalized communities.

About the Translator

Thangeswaran is a Tamil poet and short story writer; his works have been compiled and published as collections.